By Dee Mullowney, MVB DipACVIM DipECVIM MRCVS American and EBVS® European Veterinary Specialist in Small Animal Internal Medicine

Here we present an Internal Medicine case report that demonstrates both multi-disciplinary teamwork between our Internal Medicine, Anaesthesia, Diagnostic Imaging and Nursing teams and our ongoing collaboration with our referring vets to facilitate chronic case management.

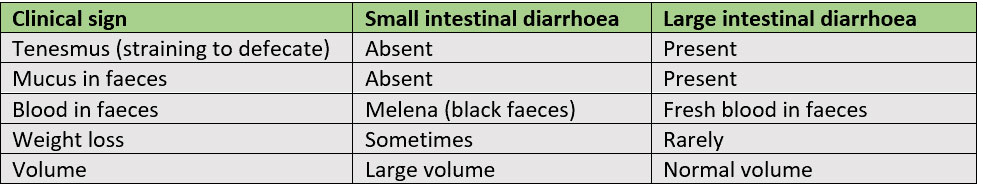

Cases of chronic diarrhoea can be challenging to manage and frustrating for owners. Although outcomes are varied, many of these cases can improve clinically with appropriate management. Diarrhoea is usually considered chronic if there is no sign of improvement after 14 days. Initial investigations of chronic diarrhoea include ruling out non-gastrointestinal causes, for example endocrine disease (hypoadrenocorticism), pancreatic disease (exocrine pancreatic insufficiency), and hepatic disease. Chronic diarrhoea should be classified as large intestinal, small intestinal (see Table 1.) or mixed in origin.

Table 1. Clinical signs associated with small intestinal and large intestinal diarrhoea

Ernie was referred to the Internal Medicine Service at Lumbry Park for further investigations of a two-month history of chronic small intestinal diarrhoea and 1.3kg weight loss in six weeks. Ernie was fed a complete commercial dog food and was up to date with flea and worm treatment and vaccinations. Investigations had been performed at Ernie’s local vets where hypocobalaminemia (cobalamin 112pmol/l reference interval [RI]; 200 – 408) and panhypoproteinemia (total protein 32g/l (RI: 50 – 72), albumin 16 g/l (RI: 26 – 40), globulin 16 g/l (RI: 19 – 46)) were documented. Concern was raised for a protein losing enteropathy (PLE) and Ernie was referred to us for further investigations.

Other differential diagnoses of hypoalbuminemia include hepatic insufficiency and protein losing nephropathy (PLN). Ernie had no evidence of hepatic insufficiency on biochemistry (Table 2.); urea, glucose and bile acids were within normal limits. Mild hypocholesterolaemia was present, however this is also a common finding in both liver and malabsorptive diseases such as protein losing enteropathies. Urinalysis including urine protein to creatinine ratio (UPC) was also performed to exclude a PLN. Many dogs with chronic diarrhoea will respond to a strict hydrolysed diet trial, however concerning clinical signs such as marked weight loss, poor body condition, muscle or hypoalbuminemia influence our decision to perform endoscopy prior to a diet trial. Endoscopy of the gastrointestinal tract is particularly useful for obtaining mucosal biopsies in PLE as these patients are at an increased risk of dehiscence following full-thickness biopsy.

Table 2. Biochemistry results for Ernie

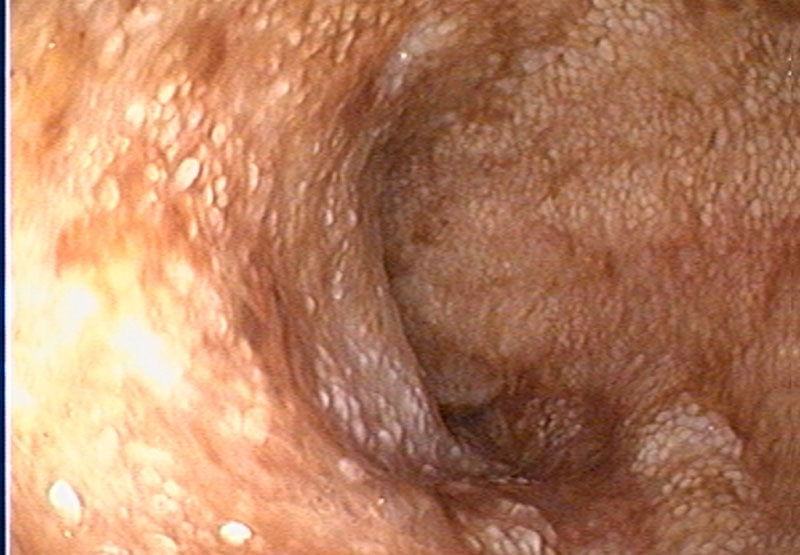

On physical examination, Ernie had mild muscle wastage and rectal examination documented liquid diarrhoea. The remainder of his clinical examination was unremarkable with a body condition score of 5/9 and normal muscle condition. Serum biochemistry documented persistent panhypoproteinemia, hypoglobulinemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypocholesterolemia and total hypocalcaemia (1.86 mmol/l RI 2.20-3.10) which was confirmed as ionised hypocalcaemia (Ca++ 1.09 mmol/L). Ionized hypocalcaemia is a common finding in cases of PLE secondary to Vitamin D and calcium malabsorption. Abdominal ultrasound under sedation was performed by our specialist diagnostic imaging team. There were hyperechoic mucosal striations visible in the small intestine (Figure 1.). This is a common finding in cases of intestinal lymphangectasia, a form of PLE. Upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed under general anaesthesia. We could see lacteal dilation in the duodenum and ileum (Figures 2 and 3). Biopsies were obtained from the stomach, duodenum, colon and ileum and submitted for histopathology which showed mild, diffuse, chronic active enteritis with mild villous blunting and lymphangectasia in the duodenum and ileum. There was also evidence of lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic enteritis and gastritis.

Figure 1. Image of abdominal ultrasound of the jejunum showing hyperechoic mucosal striations

Figure 2. Ernie’s duodenum showing evidence of hyperaemic mucosa and dilated, fat-filled lacteals

Figure 3. Ernie’s ileum showing evidence of lacteal dilation

Intestinal lymphangiectasia is characterized by marked dilation and dysfunction of intestinal lymphatic vessels. Abnormal lacteals rupture, and protein-rich lymph leaks from villi into the intestinal lumen resulting in hypoalbuminemia. Some patients with lymphangectasia will respond to a fat-restricted, calorically-dense, easily-digestible diet. We discharged Ernie from hospital with instructions to feed an exclusive diet of Royal Canin low fat gastrointestinal food. Dogs with hypoalbuminemia are predisposed to forming blood clots so we dispensed an anti-platelet drug (clopidogrel) to be given until serum albumin concentration normalised. We also prescribed cobalamin supplementation to treat his hypocobalaminemia, a common finding in cases of PLE as the diseased intestine fails to absorb cobalamin. Ernie initially showed improvement and when he revisited Lumbry Park two weeks later, his hypoalbuminemia had improved and diarrhoea had resolved. Sadly, one month later, Ernie returned to his local vet as he had a recurrence of diarrhoea. Serum biochemistry documented a worsening hypoalbuminemia. Ernie’s local vets contacted us for advice and we recommended a tapering course of immunosuppressive dose of prednisolone (2mg/kg once daily for two weeks and then reduced by 20-30% every 2-3 weeks as long as clinical signs and hypoalbuminemia remain in remission) as Ernie also had lymphoplasmacytic enteritis and gastritis which could represent concurrent inflammatory bowel disease. Thankfully, Ernie’s clinical signs and albumin levels subsequently improved.

Figure 4. Ernie feeling better at home!

This interesting case demonstrates the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to complicated cases with collaboration between the Internal Medicine Service, Diagnostic Imaging Service and Anaesthesia Service. We also maintained communication with Ernie’s local vets to provide ongoing advice to maximise management of Ernie’s disease. The Internal Medicine Team are happy to discuss or accept referral any of your challenging gastrointestinal cases. Please do get in touch.